(شجرة التمائم،Amulets tree)، للكاتب: محمد حمد | السودان

ترجمها إلى الإنجليزية: مصطفى آدم | السودان

شجرة التمائم

أخي الأكبرُ ماتَ بعدَ تسعةِ أيامٍ مِنْ ولادَتِهِ، حيثُ لم يجفْ جيدًا دمُ العقيقةِ المُهْرَقُ تحتَ شجرةِ الحرازِ ولا مشيمتُهُ التي كانتْ تُؤيِهِ، تركوا كلَّ الملابسِ المُجَهَّزَةِ له والمناشفَ والكشاكيشَ، لفوهُ بكفنٍ صغيرٍ، وبعدَ دفنِهِ دعوا اللهَ أن يكونَ سلفًا لوالديه، عندما عادوا إلى البيتِ كانَ دمُ العقيقةِ قد جفَّ تمامًا على هيئةِ خارطةٍ قانيةٍ لبلدٍ مجهولٍ، بلدٍ بلا اسم يحويهِ، مثلي تمامًا.

أختي التي تلتْ أخي ماتتْ بعدَ ثمانيةِ أيامٍ، وكأنَّها انتظرتْ أنْ تأخذَ اسمَها لتذهبَ بِهِ. كانتْ تمتصُّ الحَلَمَةَ باعتياديةٍ، ثم توقَّفتْ دونَ سببٍ واضحٍ، يبدو أن الموت أتاها دونَ علاماتٍ ولا تفاسير. تحتَ شجرةِ الحرازِ كانَ إمامُ المسجدِ يسردُ لأبي أوصافَ الجنةِ مواسيًا بأنَّهَا لبنةٌ من ذهبٍ ولبنةٌ من فضّةٍ، وملاطُها المسكُ الأذفرُ، وترابُها الزعفرانُ، وحصباؤها اللؤلؤُ والياقوتُ، بينما اكتفى البقيةُ بمصافحَتِهِ وترديدِ دعاءِ “اللهم اجعلْهَا سلفًا وعِوَضًا”.

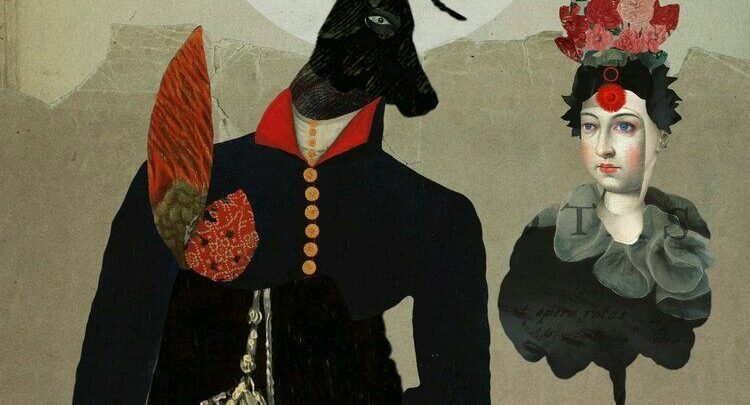

انفضَّ العزاءُ الصغيرُ سريعًا بلا دموعٍ، الحزنُ يُرَابِضُ في الذاكرةِ المشتركةِ، لا في الفقدِ المحضِ، تفرَّقَ الرجالُ لشئونهم بينما النسوةُ ظللنَ مع أمي لأسبوع، يردِّدْنَ “إنه القضاءُ والقدرُ” لكنّه مع فعلِ ساحرٍ وتحريضِ حاسدٍ، وكيدِ كائد. تعوَّذْنَ مِنْ شرِّ النفَّاثاتِ في العُقَد، وطفقنَ يبحثنَ عن التمائم المدسوسةِ بشقوقِ البيتِ والكُوَى والثقوبِ الصغيرةِ، ولأنَّها تمائمُ خارقةٌ سُدَّتْ عن أعينِ المُنَقِّبِينَ، وتوارتْ داخلَ رأسِ أمِّي.

لأنَّ الحياةَ لا تكترثُ بمنْ هبطَ، صعدتِ الشموسُ تلوَ الشموسِ، وتصاعدتْ الضحكاتُ، وتضوَّعَتْ المباخرُ في البيتِ، وتصاعدَ حطبُ الطَّلْحِ مِنْ حفرةِ الدخانِ، ونَمَتْ أفرعُ شجرةِ الحرازِ قليلاً بطلْعِ النوَّارِ، وتصاعدَ صوتُ الكابلي على راديو “هنا أم درمان” يغنّي {دوارةٌ شمسُ الضحى على مَهَلْ/ في خطوِها المرصودِ يندسُّ الأَجَلْ/ لولاكَ يا محبوبُ ما كانَ الأملْ/ حسنٌ وحزنٌ واشتهاءٌ لا يُمَلْ} وفورَ نهايةِ الأغنيةِ شعرتْ أمي بأنّي أتخلَّقُ برَحِمِهَا، أَنْزَلَتِ الطعامَ من النارِ وحَلَّ قلقُها محلَّه.

أكبرُ كلَّ يومٍ وأجتازُ الأطوارَ: نطفةً فعلقةً فمضغةً وأتمدَّدُ، بينما تهرعُ أمّي للقبابِ المُزَيَّنَةِ بالأخضرِ، أسمعُ هزيمَ الطارِ والنوباتِ وأصواتَ الدراويشِ المجذوبين المُعَذَّبِينَ بالوَجْدِ، بالتوقِ العظيمِ، وبالحب الإلهيِّ المُنِيرِ. أسمعُ همهماتِ الأسحارِ النورانيّةِ ورفَّ الأعلامِ، ثم تمدُّ يدَها عاليًا تنادي الصالحينَ والأقطابَ وتمسحُ بها على تكويني/على تكويرِهَا، تارةً أسمعُ صوتًا غليظًا وجافًّا يتلو علينا الرقيةَ الشرعيةَ، ويقول لها إنَّ العينَ اللامّةَ صنوُ بُعْدِ النساءِ عن العقيدةِ الحقّةِ، ثم يتعوَّذُ باللهِ من النساءِ والشياطينِ والدركِ الأسفلِ من النارِ، وتارةً أسمعُ الطلاسمَ الغامضةَ وأحسُّ بدمِ الديكِ الأسود السخينِ المذبوحِ على بطنِهَا، وتارةً تجتمعُ النسوةُ حولَ الإيقاعِ الصاخبِ والرقصِ المجنونِ يستدعينَ بشيرَ، واللوليةَ، وعيدروسَ الساكنَ عدنَ، وبلالَ الساكنَ الجبالَ، ويطرقنَ بالدفوفِ علي أبوابِ الشرقِ والغربِ وأبوابِ الريحِ، ويطلبنَ منها النزولَ، ومن ضيوفِهِنَّ العفوَ والرضاءَ والشفاءَ، على اللهِ وعليكم.

عندما اقتربَ طَلْقُها أحضرَ أبي نعجةً بدلاً من الكبش، وحضّرت أمي مخاوفَها المتناميةَ كلَّهَا لولا أن وقفَ رجلٌ مُسِنٌّ خلفَ نافذةِ المطبخِ، كأنَّهُ قادمٌ من سفرٍ بعيدٍ، لكنْ لم تزلْ عيناه بَرَّاقَةً كعيني طفلٍ، وقال لها بصوتٍ مُهَدَّجٍ: “لا تُسميهِ بأيِّ اسمٍ ولا كنيةٍ حتى يبلغَ الحُلُمَ” ثم ابتسمَ ابتسامةَ الذي سيختفي بغتةً، بعد أنْ مَدَّ لها ثلاثَ بلحاتٍ لَيِّنَاتٍ لولاهنَّ لظنَّتْ أنه حلمُ المُتَمَنِّي المُرْتَابِ. انْفَسَحَ الخبرُ حتى الربوعِ البعيدةِ كأنه ريحٌ مريحةٌ، وحتى بعدَ ولادَتِي بعشرةِ أعوامٍ كنتُ أسمعُ قصَّتِي وكأنَّها حَدَثَتْ قبلَ قليلٍ، ونموتُ وسطَ حذرِ الجميعِ من مُناداتي بأي اسمٍ ولا صفةٍ عدا بعض المتفلِّتينَ الذين يقولون لي أسماءً تعني فيما تعنيهِ أنَّنِي بلا اسمٍ، مثل (سليقة/بدون/ساده/ساي/أمفكو) لكنها تختفي سريعًا.

ياءُ النداءِ وحدَها كافيةٌ لأنتبِهَ، ياءُ النداءِ المبتورةُ، غيرُ المتبوعةِ بشيءٍ، صرتُ المُنَادَى المُعَرَّفَ بالإطلاقِ، المُضمرَ بالرغمِ مِنْ حُضوري، المُسْتَتِرَ بالرغمِ مِنْ وُجودِي. أتركُ مِن اليمينِ مسافةً خاليةً لاسمي الذي سيكون، مُتبعَهَا باسمِ أبي الذي تُوفِّيَ وخَلُد معي اسمُه، ثم أتركُ المسافةَ منَ الشِّمَالِ في دفترِ اللغةِ الإنجليزيةِ، أنا الغائبُ في كلِّ اللغاتِ والصفاتِ الكونيّة، عندما تنادي الأستاذةُ اسمي مُمازِحَةً Hey Mr Absent أنتبهُ إليها، إلى شفتيها، إلى تضاريسِ صدرِهَا، ثم في مرةٍ انحسرَ الثوبُ عنها فَفِضْتُ بِهَا، وفي أحلامي كانَ ينحسرُ أكثرَ فأفيضُ حتى اللحظةِ الراعشةِ اللذيذةِ التي ما إنْ بَلَّلَتْ سروالي عَرفتُ أنني استحققتُ اسمًا بعد كلِّ تلكَ السنواتِ التي فُتِنْتُ فيها بأسماءٍ كثيرةٍ لأنبياءَ وفضلاءَ وثوارٍ ومُغَنِّيينَ وشعراءَ وممثلين، أخيرًا سَأُسَمَّى، وكنتُ أتمنَّي أن تسميني أمي، لولا أنْ تخطَّفَتْهَا حُمَّى السحائي قبلَ أشهر.

كتمتُ سِرَّ بلوغي لأشهر؛ لأختارَ من الدفاترِ الكثيرةِ التي دونت فيها الأسماء جميعها، لكن صوتي بدأ يفضحُني، ثم بدأَ حماسُ أهلِ الحيِّ في التصاعدِ لإكمالِ قصَّتِهم/قصَّتِي المعلقةِ، الناسُ تحرِّقُهم القصصُ الناقصةُ، اسمي ختامٌ وموتي ختامٌ، والحصادُ ختامٌ، ولكلِّ مبتدإٍ مُنْتَهَى، لكلِّ شئٍ دورةٌ، ولكلِّ خريفٍ سِماك، ولكلِّ صيفٍ ذِراع، ولكلٍّ شتاءٍ نعائم. آثرتُ عدمَ الخروجِ؛ لكثرةِ السؤالِ والإلحاحِ، فأصبحتُ لا أجيبُ علي منادٍ، ولا أشرعُ بابي لطارقٍ، أريدُ اسمًا بشدَّةٍ؛ حتى أتعبَ من التحديقِ في الدفاترِ، ثم لا أريد.

أنتخبُ أسماءً بسرعةٍ، ثم أسقطُها، حتى جُهِدَ عقلي، رفعتُ بصري للسماءِ، وعندما أنزلتُه تعثَّرَ برجلٍ متبسمٍ يجلسُ تحت شجرةِ الحرازة، قال: ما يضيرُكَ لو أنَّ اسمَكَ اسمُك أو اسمَك ضدُّه، التعريفُ قيدٌ وتكليفٌ يا (يا)، كُن النداءَ لا المُنَادَى تكُن الأسماءَ كلَّها، كُن البلدَ القاني المجهولَ تكن الجهاتِ كلَّهَا، الأبوابُ كلُّها الشرقُ والغربُ والريحُ والمواسمُ هل تريدُ؟ أومأتُ برأسي كثيرًا، ثم بسطَ كفَّهُ بثلاثِ تمراتٍ، أخذتُها وبدأنَا نتسامَى فوقَ شجرةِ الحراز، فوقَ التمائمِ والطلاسمِ، فوقَ القِبَابِ والراياتِ جميعِهَا، فوقَ حَذَرِ المُرْتَابِين من الذنوبِ، فوقَ بلال الساكنِ الجبالَ، حتى أصبحت المعالمُ بلا أسماء، بلا حدودٍ فاصلةٍ، بلا فوارقَ واضحةٍ، ثمَّ أشارَ بالوصولِ.

▪▪▪

Amulets tree

Translated by: Mustafa Adam

.

My first-born brother passed away after just nine days from his birth. The blood of the sacrificial sheep slaughtered under the Haraz tree, on the seventh day name-giving ceremony, had not dried up altogether, as well as the placenta in which he dwelt for nine months. They left behind all the baby’s clothings, home-made diapers and jingling toys, specially prepared for the then forthcoming baby. They shrouded the small body in a white fabric and, after burial, they prayed to Allah to reward his parents. When they returned home from the burial ground, the blood of the sacrificed sheep had completely dried up in the outline of a sanguineous map of a nameless land, just like me.

My second-born sister had passed away just eight days after her birth, as if she had waited just enough time to take her name into the heavens with her. She suckled her mother’s nipples nonchalantly, then suddenly stopped for no apparent reason. It seemed that death had taken her by surprise, without any signs or symptoms of her emanant death. Under the Haraz tree, the Imam of the mosque was relating the descriptions of paradise to my bereaved father, in an attempt to solace him, saying that the edifice is built with one golden brick followed by another silver one, stuck together by fragrant musk mortar and its soil is made of Saffron and pebbles of precious pearls and sapphires. The others made do with shaking hands with my father, repeating, waveringly, the trite prayers routinely said in such sorrowful occasions. The little funeral dispersed quickly without much ado and without shedding a single tear. Grief lurked everywhere in the collective memory of the people but not in the forlorn pure sense of loss. The men went their different ways pursuing their own small businesses, while women remained in the company of my mother for a whole week, repeating, almost to themselves rather than to my mother, that it is predestined. Yet, in their innermost thoughts, they believed that it was the meddling of black magic, sorcery and the instigation of envious ones and ill-intentioned wily agents. They sought refuge in Allah from the evil of malignant witchcraft and hastily started looking into potential hiding places to dig out the evil amulets. They looked into the cracks, slits and small holes in the house walls, and because of their being super potent ones, they were, probably, secreted in the very brain of my mother.

It is in the nature of things that what is buried below the surface of the earth is soon forgotten. Because life is not very much concerned with those who vanished, many shining suns have risen, one after the other, laughter resonated in the corners of the house, incense holders infused fragrant smoke in the air and the smoke of Shaff and Talih wood engulfed the whole house. The branches of the Haraz tree had grown a little bit larger, with pollen blossoming, accompanied by the voice of Al-Kabli ensuing from Om Durman radio singing: “ The forenoon sun spinning gracefully at its ease; in its monitored movement, destiny is secreted, if not for you my loved one, there would be no hopeful anticipation, gracefulness, sorrow and unceasing craving”. And immediately after the end of the song broadcasting, she felt like I was becoming in her womb. She took the cooking pot, in which the dinner was peacefully simmering, off the fire, and in its place her trepidation was squarely placed.

I grew by the day, passing through fetus stages; drop of life-germ; then an embryonic clot and then a lump of flesh, growing bigger. While, my mother was busy rushing to visit shrines of holy men and saints, embellished with green decorations, I had to listen to the rumbling of tambourines; the pass drums and the voices of dervishes in spiritual trance, grappled by the ecstasy of passion and imposing yearning for luminous divine love. I had to listen to the humming of incandescent charmed chanting and fluttering of flags. She would stretch her hand high enough, in supplication, to call upon the dead righteous holy men and spiritual magnates, and then rub her hand, gently, on me, becoming within her protruding womb. At other times, I could hear a deep dry voice loudly reciting religious incantations to dispel spells and the evil eye and telling her that the evil eye is a direct result of women’s distancing themselves from true faith and goes on making various recitations for seeking refuge in Allah against women, devils, evil spirits and the lowest depths of the Fire (hell). At some other times, I would listen to outlandish talismans and felt the tepid blood of a black rooster slaughtered on top of my mother’s belly. At so many other occasions, I would hear women congregating around the noisy rhythm and the crazy dancing summoning Bashir, al-Loulyia, and Aidarous; who takes his abode in Aden, and Bilal who takes his abode in the mountains, beating on timbrel and tambourines at the gates of both the East and the West and the Gates of the Wind, calling upon them to descend, asking forgiveness and acceptance from their summoned masters and guests and requesting the healing of the sick, relying on Allah and their masters, concurrently.

By the time of the expected labor and my delivery, my father brought an ewe, instead of the ritualistic ram. My mother prepared her loaded growing fears, if not for the fact that an elderly man appeared from nowhere, stood by the kitchen window, and looked as if he had traveled a long journey to arrive on time for the occasion. Though fatigued, he had the glowing glint of a small baby. He told her, in a quavering voice; “Don’t give him any name or a nickname whatsoever until he reaches puberty”. He painted a faint smile, like someone who was about to disappear suddenly into thin air, after he handed her three soft dates. If not for the corporal dates, one would deem the whole episode as a part of a strange dream of a skeptically wishful person. The news was spread far as if by ethereal wings of a comfortable wind. Even ten years later, I would listen to the notorious story of my birth related as if it had just happened afresh. I grew up amidst the apprehensive fear that someone would call me by any name or description, apart from the foolhardy, who would call me by names denoting that I was nameless, such as “ saliqa”; “ Bidoun”; “ Sadah”; “ Saai”; or “ Amm Fakko”, but such labeling would soon vanish altogether.

The Arabic vocative article was quite effective to draw my attention to any one addressing me; the truncated vocative “Ya”, unfollowed by any noun. I was the vocative case, defined by the implicit designation despite my physical presence, hidden despite my actual existence. At school, I started leaving sufficient space for my non-existent name at the right margin of the page, followed by my father’s full name, who died leaving behind his immortalized name. When I started learning English, the same procedure applied but, in this case, leaving the blank space at the left side of the page in my school notebooks. I was the third person singular in all universal languages and descriptions. When the English language teacher would address me teasingly, she would say: “Hey Mr. Absent”, I would pay full attention to her, focusing my eyes on her rounded lips and the curves of her breasts, and, in one occasion, her tobe was unintentionally dropped, I was overwhelmed by her beauty. In my dreams, her dress was drawn even further down, with the foregone result of recurrent consummating sweet wet dreams. I realized then that the time had come to be given a proper name. After all these years of deprivation, in which I was fascinated by names of prophets, sages, revolutionaries, celebrities among poets, singers and actors, at last I was going to have my own name. I was hoping that my mother would be there, presiding over the rite, but, unfortunately, she was snatched away by the deadly Meningitis, a few months before that momentous occasion.

I had kept the secret of my reaching puberty to myself for a few months, to have enough time to pick a suitable name from the numerous notebooks in which I had been jotting down all the names. However, the changes in my voice gave me in. The fervor among the people of the neighborhood, for finally putting an end to my unfinished story of suspended naming, gathered momentum by the day. People usually turn irksome and are exasperated by unfinished tales or suspended ending. My naming is a conclusion; my death is an ultimate end, and harvest is consummation of a cycle. Each beginning has an end. Everything is cyclic; every Autumn has its Simak ; every Summer has its Zira’a and every Winter has its An-Na‘āʾam. I had opted for staying indoors in order to avoid the urgent enquiries and questions. I didn’t answer the knocking at my door. I desperately wanted a name of my own to put an end to the consuming search into my notebooks full of names, then I would change my mind about wanting a name altogether.

I choose a number of names hurriedly, then drop them to the degree of brain fatigue. I raised my eyes into the sky for help and when I lowered my head, I stumbled on a smiling face of an elderly man sitting under the Haraz tree. He said gently: It wouldn’t hurt you if your name is your name or its opposite. Definitiveness is shackles and arduous burden oh “Ya”. Be the vocative case but not the addressee, you will be the names, all of them; be the sanguineous nameless homeland; you would be the directions, all of them together; all the gates, the East, the West, the Wind and the Seasons. Would you opt for that? I nodded yes fervently, then he opened his palm offering me three dates. I accepted his offer and we started ascending together, first, over the Haraz tree, then above the talismans and amulets; above the green shrines and fluttering flags, all of them, over the precautious irksomeness of souls laden with suspicion of being sinners; above Bilal, who takes his abode in the mountains, until landmarks turned nameless, without delineating borderlines or distinct differences. Then he indicated the gesture for our final arrival.